Data has turned into a business discipline, across organisations. But data excellence is a long and winding road and hillier than the one that leads us to the digitalization of our personal and professional lives. In the world of data, the trick is that there has been no equivalent of Facebook, LinkedIn, Google, Zoom, or Slack to standardize new ways of working or interacting.

However, there has been a considerable increase in skills, to the extent that data specialists appear in the top 25 most sought-after professions in France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, the UK, and throughout Europe in 2022 according to LinkedIn. A whole ecosystem of specialists was established early on, across software providers, consultancy boutiques, and integrators, and in the end-user companies themselves. Every piece of the puzzle should be in place to reach the mainstream. Unfortunately, you shouldn’t expect an out-of-the-box solution to drive you toward the data-driven enterprise: This is on you to shape and drive your own journey.

A successful data initiative is about creating a socio-technical system, a network woven between economic and social players around a product or service. Many companies have now reached a sufficient level of maturity to establish such a system, which is able to promote continuous innovations when they are consistent with its operation while blocking those that do not fit in.

Taking a commonsense approach to data: this is what makes our job exciting, but also challenging. This requires relying on three levers of progress: organisation (which is the focus in the first part of this blog), together with architecture, and governance (addressed in the second part).

Establishing the data discipline with a data office

According to PWC, 42 % of European companies have a Chief Data Officer (CDO), a figure that has increased by 75% since 2021. In addition, many others have set up a dedicated data office or centre of expertise, whose remit has grown in scope and whose leaders have gained decision-making power. But they also face significant challenges to the point where the average longevity of a CDO in their position is currently less than two years.

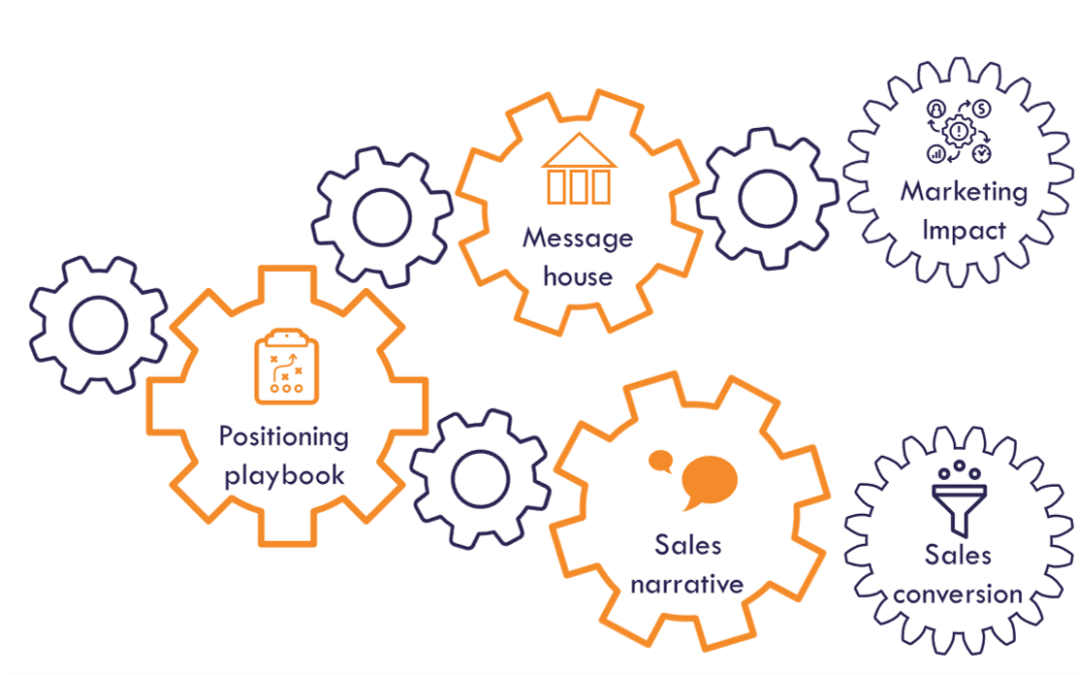

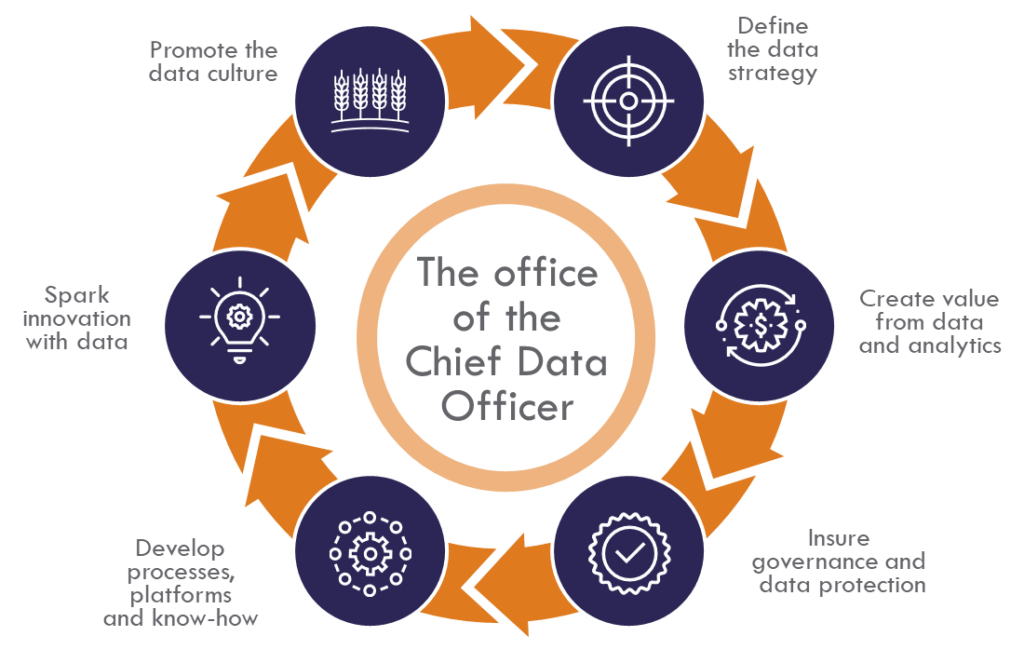

The data office has an important role to play in the journey to a data-driven organisation. Its primary role is to establish the strategy and the roadmap, find out how to apply data against the business challenges, and how to make it happen concretely. The purpose is also to progress along the maturity curve by recognising the weaknesses and the desired areas for improvement.

It is also important to find ways to associate data with business value, prioritise initiatives and business domains while developing the core best practices in analytics, supported by multi-disciplinary teams, who do not necessarily report to the data office, but who can engage early with those who consume data to serve their business.

The data office also faces the heavy responsibility for establishing governance, the biggest challenge, because it has to be both an agent of change and a controller. As the value of data has increased, it is not only a matter of sharing it, but also of protecting it, securing it, and managing the risks: data governance requires mastering the art of compromise by combining defensive and offensive strategies.

Beyond governance, to perpetuate usage in the company, the data office must also create the foundations and the critical mass, and for this reason, it generally operates as a shared service centre. In this way, it can frame the target operational model, together with the best practices, methodologies, standards, and platforms, but also an environment that is favourable to the development of talent, from the definition of roles to training, recruitment, and career development.

It must also serve as a breeding ground for innovation, through a data lab which operates as a multi-disciplinary unit for experimenting with innovative ideas or use cases in a try-and-fail mode, without hampering the necessary industrialisation of more mature data initiatives.

Finally, the data office is the change agent that spreads the data culture throughout the company. In the digital world, we saw a peak of Chief Digital Officer, followed by a decline when the most mature organisations considered that the transformation effort had now to be led by the broader organisation. And this may also be the destiny of the data office and its Chief Data Officer: behave as a facilitator for the gradual rise of increasingly decentralised organisations once each activity have gained maturity in its ability to produce and consume data autonomously.

Decentralising data management for widespread use: the data mesh promise

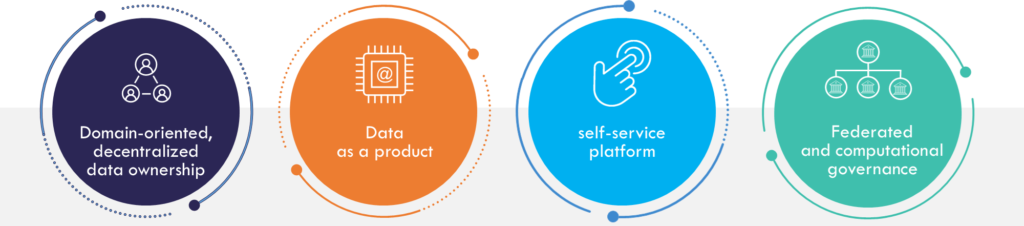

Hence the fact that data mesh principles are in the air: introduced in 2019 by Zhamak Dehghani, who was then in charge of the distributed systems architecture practice of a major consulting firm, they put a mischievous kick in the data ecosystem’s anthill. The data mesh promotes a decentralised approach for data initiatives, by immersing its specialists in business domains rather than by involving the business in data initiatives. The goal is to solve what has become an organisational pain, pointed out by a BARC study highlighting gaps when data initiatives are delivered through centralized IT or data teams: 65% of decision-makers regret that business domains have no data responsibility, and 53% that business domain expertise in IT/data & analytics teams is insufficient.

Data mesh principles resonate to organisations that have reached a milestone in their data maturity curve when it is time to delegate data responsibility to the business domains. To achieve this, data mesh takes inspiration from the domain-driven design approaches used in the software world.

The second data-mesh principle, data as a product, is also borrowed from the software. Applying product thinking to data aims to facilitate its consumption by making it more easily understood, findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable. Another goal is to productize and improve the quality, by imposing the rigour inherited from product management practices on the design and management of their life cycle, from roadmap to documentation and service level agreements.

While the two first principles disrupt the way data initiatives are approached, the two others can be seen as prerequisites that make them fully applicable to the context. Even when they decentralised, data products need to be universally accessible across the board, as a self-service. While the two first principles disrupt the way data initiatives are approached, the two others can be seen as prerequisites that make them fully applicable to the context. Even when they decentralised, data products need to be universally accessible across the board, as a self-service. This third principle is nothing new to the data world, but it has not developed as fast as we might have expected. However, the more data is produced in a distributed manner, the more essential it is to have a universal mechanism that allows everyone in the company to consume it autonomously, without friction or dependence on intermediaries. Think of the web where search engines became essential points of passage for accessing the web.

Finally, the fourth principle relates to governance. The more we distribute the responsibilities over data, the more we need to establish common rules, while their application needs to be monitored. Federated data governance must be put in place, and scaling its control requires automation whenever possible.

The merits of the data mesh are that it brings the guideline. As with the principles of data warehousing and data mart laid down by Bill Inmon and Ralph Kimball in the 1990s, the guideline is not a recipe for success, but a source of inspiration for bringing data initiatives to a higher level of maturity. Zhamak Dehngani defines the data mesh as a system of scale. It might be counterproductive to try and apply until a certain level of data maturity and critical mass has been reached. You need enough data experts before dispersing them across functional areas, while still being able to control through federated computational governance. Not all organisations are ready for the data mesh, but this can be their North Star as they progress on maturity, knowing that the founding principles of which can be adopted incrementally.

Ramping up through the organisation, but also through architecture and governance

In the first part, we focused on the organisation. In the second part of this article, we will look at architecture and governance.

This article is based on a presentation made for the keynote of the KPC consulting data days in Paris. Click below to access the full presentation.